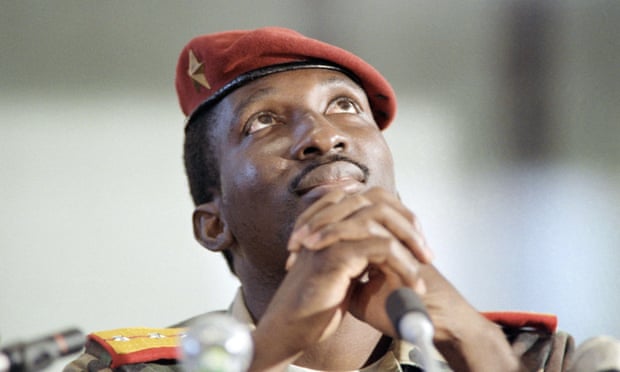

Thomas Sankara, the first president of Burkina Faso,

was born in a rich family in French colony Upper Volta. He joined the army as

young people at that time thought army was a progressive power against

corrupted French-control bureaucratic government and powerful tribal order (Peterson

2021). His teacher Adama Touré, who deeply believed in socialism, taught

him about the revolutions in Soviet Union and China. In his study in Madagascar

and Morocco, he began to learn professional knowledge of agriculture and got a new

friend, who was also his best friend, Blaise Compaoré. In 1983, after two coups

led by Compaoré against Zerbo and Ouédraogo, he became the prime minister of

this country and began his reform, especially toward its food crisis (Peterson

2021).

|

| Guardian 2015 |

The food shortage of Upper Volta came from three

sources: the high proportion of land for cash crops, the extremely unequal

spatial distribution of precipitation and river discharge, and the expanding

desert from the north. Instead of employing independent projects like

building dams to increase irrigation and food production, Sankara solved all of

these problems systematically (Peterson

2021).

He first changed the land ownership from the hands of large landowners to local farmers to provide more land for subsistence crops. In the next step, Sankara cut useless expenditures such as expensive cars for further investment including subsidies for subsistence crops, imports of fertilizers, and construction of irrigation systems. In just two years, the total food production reached 1.6 billion tons a year which totally eliminated famine in this country (Le Monde 2020). Later he advocated the planting of trees to protect the agricultural fields from the expanding desert and the construction of roads across the country to improve food transportation efficiency.

Meanwhile, he also pushed forward other development

projects in multiple fields including education, women's rights, and disease

control which indirectly increase the food productivity in this country. Within

his leadership, this country was moving toward a better future (Peterson

2021). In this situation, he changed the name of this country from Upper

Volta which is a totally geographical name to ‘Burkina Faso’, which means ‘the

land of upright people’ (Burkina

24). Unfortunately, after four years of being president, Thomas Sankara was

betrayed and assassinated by his best friend Compaoré with support from the

French government.

|

| National Flag of Burkina Faso |

|

| National Flag of Upper Volta |

In the next few years, with ‘guidance’ from the West, the Burkina Faso government follows neoliberalism and gives irrigation systems to the local communities and private sectors (OECD 2013). Although this model proved to be more efficient in using water resources, the inter-communal conflicts it supports and increasing cash crop land area cause increasing food shortage and at least 3.4 million refugees inside (IFRC 2022). With all the policies against Thomas Sunkara’s communist approach, this country falls back into the trap of food insecurity and underdevelopment.

The next two blogs will focus on the current situation

in Burkina Faso which will focus on the community and private sectors separately.

Book: Thomas Sankara: A Revolutionary in Cold War Africa, Brian J. Peterson 2021

Video:

You post demonstrated a reasonable grasp of water and food issues in Africa, and engagement with relevant literatures. Well done on these posts, and one suggestion will be to try and stick to specific region or case study, Somalia or Ethiopia would have been grear or even Burkina Faso. Not all the references were embed as link, as such this need to improve in subsequent posts.

ReplyDeleteYour post on water and food in Africa: A story of despair and hope was in italic, which makes it difficult to read. However, you mentioned about “the continuous conflicts between Ethiopia and countries around it”. What type of conflict? Is it over access to water and food? Also, this claim that “the relationship between water and food is a miniature of development in Africa: the legacy of colonialism and the unequal international systems is still exploiting different kinds of resources from Africa” deserves explanation and case study evidence. And a focus on Somalia or Ethiopia will be great but not both at once in one post.

The post on sall Scale Groundwater Irrigation: the Future for Africa Agriculture? Hilighed groundwater irrigation (GWI) adoption in Africa, which also raise question about what are the implication of the growing adoption of GWI on available water supply? The assertion about ‘Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria adopting GWI requires evidence and clarification about specific challenges and opportunities.

In the the third post on What is lack for African food crisis depicts irrigation system, you made three statements that need to be reconciled: 1.“Ethiopian people died in the famine in the 1980s while the Somalian people also suffered from catastrophic famine in the 1990s”, 2. “One of the most important reasons for the current crisis is the lack of irrigation systems including local systems like groundwater irrigation (GWI) and national systems like huge dams and channels to store and transport water”, and . 3.“But at the same time, there is another problem to raise: if the irrigation system in Africa reaches the level that could properly produce enough food for all African people, would that solve the food crisis in Africa? The answer is obvious: simply no”. Water and Food challenges in Africa cannot be solved by a single approach, be it irrigation, import, subsidy or policy.

The post on The origin of the name ‘Burkina Faso’: a story of food sovereignty, security and self-sufficiency is interesting but does not give adequate representation of the current water and food challenge in Burkina Faso. Since the resolution of the three historical sources of food shortage, has Burkina Faso become water and food sustainable? What are the new challenges that Burkina Faso contend with in relation to Water and Food.